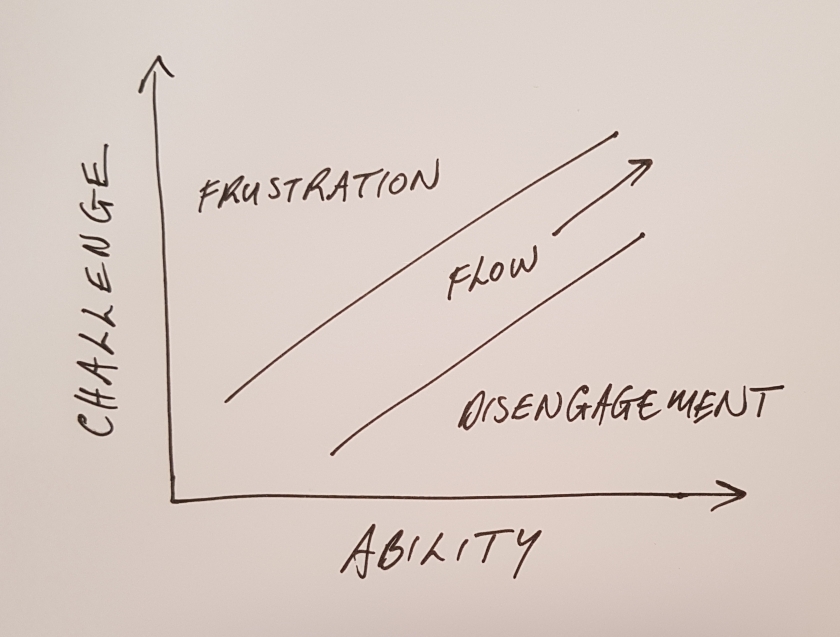

A couple of posts ago (The Zone of Opportunity) I mentioned the concept of ‘flow’, coined by psychologist, Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. Broadly, flow is the mental state that emerges when your abilities match the specific challenge of your activity. When someone achieves the balance between challenge and ability they experience complete absorption in what they are doing and thereby lose all track of time and sense of their surroundings.

Flow is a state humans seem to find innately pleasant and intrinsically rewarding. Too much challenge, or too little ability and the task is unachievable and frustrating; on the other hand, too little challenge or too easy a task will likely lead to boredom and disengagement. So to maintain flow we tend to seek increased challenges to exercise increasing skills. I have sketched this evolution here:

One role for a coach / teacher / manager is to help you select appropriate challenges and skill development to create a feedback loop which will sustain flow enjoyment of a particular skill. This is what distinguishes a flow state from a simple ‘comfort zone’.

One of the reasons learning something new can be challenging is because it is initially difficult to achieve a flow state with a novel skill. Re-engaging with something of which you have had some mastery can be more difficult, since you can perhaps recall previous flow states and be impatient to get back there.

For example I have found revisiting the fundamental skill of free-hand drawing with a U3A class a bit challenging – my engagement with this was longer ago than I first thought – I had dated one of these drawing books acquired during that period as 1993 – that’s over 20 years ago, how time flies! It was hard to find any semblance of flow with new people in a new place, doing something you are not very well practiced at – challenge high / ability low. But understanding the dynamic, and strongly feeling the need to relearn the basic skills of seeing and constructing images by hand, I will persist.

For example I have found revisiting the fundamental skill of free-hand drawing with a U3A class a bit challenging – my engagement with this was longer ago than I first thought – I had dated one of these drawing books acquired during that period as 1993 – that’s over 20 years ago, how time flies! It was hard to find any semblance of flow with new people in a new place, doing something you are not very well practiced at – challenge high / ability low. But understanding the dynamic, and strongly feeling the need to relearn the basic skills of seeing and constructing images by hand, I will persist.

I have experienced and managed that kind of discomfort at various times in my croquet trajectory – which is far from maxing out the challenge / ability curve and delivering flow in every game! One thing I have observed of myself and others on the same curve is that in the urge to improve performance or the desire to solve various problems of technique or game tactics can lead to a search for ‘magic’ solutions, a ‘silver bullet’.

The thing is croquet, like much of life, is a mean-reverting probabilistic exercise. Let me unpack that 😉

Much of what we experience has a significant random element, and we exaggerate the degree of control we have over events. So any given intervention may coincide with a better result, whether or not it has objectively increased our chance of success. But if we think it has worked – even once is enough – that intervention can then get cemented into how we play the game (or whatever else we may be doing).

This is illustrated in the idea of the placebo effect associated with minor surgery, discussed in a Guardian piece – When surgery is just a stitch-up. Andy Carr, a professor of surgery at the University of Oxford is quoted: “People with arthritis of the knee or recurrent sore knees will have good times and bad times. If you see them at a time when their symptoms are particularly bad, then any time after that their symptoms won’t be as bad. It fluctuates, but people incorrectly associate the surgery as something that caused their pain to get better.”

Placebo effects aside, the fact is that things tend to get better on their own, or given its fancy medical name, regress to the mean. Prof Carr notes that this misapprehension applies to surgeons as much as patients – “Surgery is taught like an apprenticeship … You don’t necessarily learn the scientific method, you don’t necessarily learn about the biases you may form about the effectiveness of a particular operation, and you end up forming the same biases that other doctors and the general public fall for by assuming causation where you see association.”

This mistaken confusion of association for cause is a constant peril in skill acquisition and practice. It is laid out neatly in a blog post I read recently, Critical Thinking By Osmosis by Shane Greenup, a fellow participant in Journalism PLUS, a UTS Creative Cluster workshop group I have been part of recently. He says:

“Successful critical thinking would include recognising that correlation is not causation” — you know this concept already don’t you? Correlation is not causation. I think that most people know this phrase, but how many times a day do you see it used to call out faulty causation? How frequently do you get to see the tool being used? How often do you get to watch this simple yet valuable tool of critical thinking being used, challenged, championed, questioned, and discussed within an applicable context in day to day life?

Being aware of and controlling for this is a key ingredient of critical thinking can guide more purposeful and productive interventions – it is not always comfortable, but almost always useful. Prof Carr acknowledges that “to tell a surgeon who has been doing knee arthroscopies for 30 years, and who has seen patients getting better, that they have just been wasting their time is very difficult.” It can be equally daunting (and futile) to try and tell a croquet player who is performing moderately well that a basic element of their game would benefit from adjustment.

That player may well continue to seek further silver bullets and risk layering into their game further behaviours which at best might be a ‘quirk’ and at worst may become a ‘bad habit’ and set a ceiling on their further development or progress in the game. Often people expect a coach to be the source of such magic ammunition. Doubtless there are many refinements to be applied and nuances to be mastered, and a good coach will be a store-house of such improving suggestions.

However, it has been my observation that rather than magic tricks, the best players seem to employ the basic skills of the game well … and consistently. Often the basic cause and effect is quite simple, if demanding in execution, and an excellent coach will know (and be able to communicate) when the bullets and tricks have accumulated to the point of setting ceiling on performance and when it is time to ‘get back to basics’.

In my personal experience recently, teaching and coaching beginner croquet has offered an excellent opportunity to revisit the fundamentals of the game: stance and stroke, the pendulum swing, stalking the target – every time. Going back to basics has also guided my attempts to sort out a nagging issue such as when sometimes I just can’t seem to hit a ball or run a hoop. The title of a book written and illustrated by the legendary NZ croquet player John Prince has always stuck in my mind – “Practice with a Purpose”. I couldn’t agree more, so long as your purpose is rooted in a sound grasp of cause and effect, and you are prepared to endure the discomfort of ‘unlearning’ some of the things which you may have thought helped you in the past.

It’s funny how when you pick a topic you start seeing references to it everywhere – reading a random LinkedIn post led me to this commentary by author of “Do The Work”, Steven Pressfield. It is characterized as a book about RESISTANCE and its place in any creative process … I have not yet read the work, but I wanted to share his glimpse of the struggle to achieve creative outcomes.

It occurs to me that what is termed resistance can be seen as loss of flow, and sometimes the most productive thing we can do is to deliberately step outside the flow, and to allow the discomfort of resistance to guide our creativity, learning and/or development in whatever skill set we are trying to excel at. That may mean a reset ‘back to basics’ – which will ultimately help us find more advanced and refined flow states in future.

I will leave you with Steven Pressfield’s words as he struggles with his writing:

By the way, this process that I’m going through now after the collapse of Draft #11 is the process I SHOULD HAVE been doing from Draft #1.

I was lazy.

I was scared.

I didn’t push myself far enough.

That’s why #11 crashed.

That’s what I’m back to Square One, reverting to basics.

That’s okay.

It happens to everybody.

So to recap …

Last week we talked about the first level (for me, at least) of a Ground Up Rewrite.

That level was about genre.

It involved identifying the genre we’re working in (again, a task we SHOULD HAVE done in Draft #1 and even earlier) and defining for ourselves the conventions and obligatory scenes of that genre … then reworking our story to align with those principles.

Level Two, what we’re talking about today, is about doing the same thing, not for Genre, but for Universal Storytelling Principles.

We go back to basics.

2 thoughts on “Back to basics”